National holidays are time for a country to take stock of itself. When that day commemorates liberty, independence, and innate rights, as does the 4th of July, it might be a good time to reflect on what the historical record tells us about the reaches of those concepts into New New England Indian Country.

The region’s Native Americans have served in great numbers in every major American conflict. During the American Revolution, military rosters included men from nearly ever Indian community in Connecticut, New York, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island.

Native soldiers and sailors joined for multiple reasons: a culture of military service, a means of employment, or from a patriotic fervor excited by the potential of revolutionary change. Their participation in the American experiment, however, came at a great cost.

Take, for example, the Mashpee Indian community in Barnstable County, Massachusetts. Mashpee men enlisted at higher rates than their white neighbors, comprising a fifth of the County’s total regiment. With thirty-six male heads of household in 1776, anywhere between twenty-four to fifty men joined the Continental forces to fight British troops.

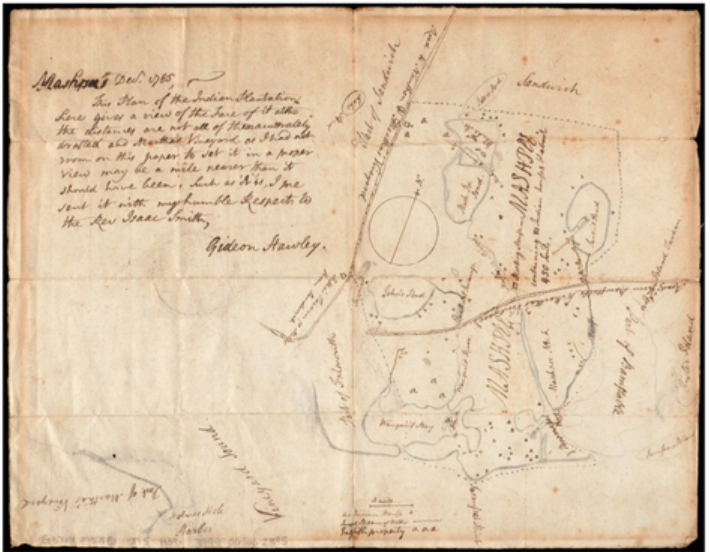

No other town in the County sent as many soldiers. Or suffered more. The Mashpee encountered casualty rates of almost 95%, leaving the community with a large number of widows, orphans, and economic hardship. By 1783, the Mashpee’s minister Gideon Hawley, observed that there were about 70 widows on the reservation, most of whom had lost their husbands during the war through combat, disease, or lingering sickness. Two years later, Hawley would draw a sketch of the community’s reservation shown above ( Plan of Indian Plantation at Mashpee).

Despite their contributions to the success of the war, the Mashpee, like many other Indian communities across the region at that time, sawno realizations of equality, independence, liberty, or democracy. Instead, the Commonwealth subjected them to a wardship system, under which personal, financial, and legal rights were managed by overseers or guardians.

The Mashpee were among the first to protest their treatment. In 1796, Noah Webquish and twenty-one of his fellow Mashpee sent a remonstrance to the Massachusetts General Court, pointing out the hypocrisy in the Commonwealth’s Indian policies.

If you have some time this weekend, please read the Petition of Noah Webquish and Other Mashpee Indians to the Legislature of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, which we have copied below. As you will find, its eloquence and force compares to the Declaration of Independence.

To the Honorable the Senate and House of Representatives in General Court Assembled.

The inhabitants of color of the District of Mashpee beg leave to offer with the utmost deference and respect the following observations to the consideration of the Honorable Legislature.

Ever since the settlement of this country, the aboriginals, and those who claimed under them, have been deemed the legal proprietors of the territory comprised within said district, the same having never been transferred or ceded to the whites. The government of the late Province of Massachusetts Bay, not withstanding, assumed the right of controlling in a peculiar manner the property and economy of said district, and imposed restraints on the inhabitants,1 which were ever considered by them as an infringement of that freedom to which as men they were justly entitled.

At the commencement of the late Revolution, when a high sense of civil liberty, and the oppressive policy of an arbitrary court roused the citizens of America to noble and patriotic exertions in defense of their freedom, we anticipated the time when a liberal and enlightened spirit of philanthropy should extend its views and its influence to the increase of liberty and social happiness among all ranks and classes of mankind.

We supposed a just estimate of the rights of man would teach them the value of those privileges of which we were deprived, and that their own sufferings would naturally lead them to respect and relieve ours. Impressed with these sentiments, and animated by a portion of that ardent sense of freedom and love of independence, which characterized our ancestors, we voluntarily entered the encrimsoned fields of battle, and freely mingled our blood with that of the early martyrs to the cause of this country.2

The sentiments and anticipations which animated us to the conflict were farther confirmed by that august and magnanimous Declaration of American Independence which appalled a British ministry and astonished all Europe. In this, these truths are solemnly stated as self-evident “that all men were created equal; that they were endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”3 The adoption of the constitution of this Commonwealth was a still farther confirmation of our hopes.4

The first article in the Bill of Rights which declares that “all men are free and equal, and, have certain natural, essential, and unalienable rights, amongst which may be reckoned the right of enjoying and defending their lives and liberties; that of acquiring, possessing and protecting property; in line that of seeking and obtaining their safety and happiness,” we expected would in future be the broad basis of freedom to all the inhabitants of the Commonwealth.

At the close of a long and successful war, in which we had been honorably distinguished and had profusely bled, how are we disappointed! How are our pleasing anticipations blasted! How could we conceive it possible that a people who were exhibiting such illustrious proofs of their attachment to freedom, and so enlarged ideas of the principles of civil liberty and of the original design of government should not respect those rights in others which they so warmly contended for themselves.

Let the acts passed previous and subsequent to the late Revolution, respecting the Mashpee Tribe be compared together, and how humiliating a comparison results. By the former, we had the miserable privilege of choosing our own masters. By the latter, even that is taken away.

Strange! that under a hereditary monarch, (and formerly considered, in this country, an arbitrary one) we should enjoy more liberty than when connected with a republican government. Instead of one master, we have now as many as there are free inhabitants in the Commonwealth, who by their representatives can make what laws for us they please.

We cannot alienate a single inch of our land, nor indeed enjoy it, as the government have undertaken to modify and apportion it as they think proper. We are legally incapable of making any contract to the amount of a shilling without the approbation of our guardians and in the choice of these we have not the privilege allowed by law to white infants of fourteen years of age. We can institute no action in our own names for the recovery of our demands. We are governed by laws enacted by a legislature where we have no representative.5

It is a fact which can be easily authenticated that one half the inhabitants of Mashpee fell honorable victims to the cause of liberty in the late contest. And many who now remain and subscribe this can show the traces of many a wound received in facing the enemies of this country.

Indeed, the District of Mashpee was the common reservoir, whence the adjacent towns drew their recruits for the late armies of the United States. When we view our bodies, lacerated and maimed, in a struggle for the liberty and happiness of others, and view our own detestable thralldom, what must be our feelings! 6 It is pretended by those who forge our shackles, that we are not capable of enjoying liberty, that we should dispose of our property without proper consideration and become chargeable to the community, that the government takes care of our property, and imposes restraints upon our conduct, merely from motives of mercy and compassion.

This is but a solemn mockery of our wrongs. How it is possible that a people who are constantly depressed by a mortifying consciousness of the inferiority of their condition, who have no incentives to industry or improvement, and who every day experience that the whites view them as objects of contempt and derision, should make any considerable figure in life? Indeed, we venture to affirm that no adequate means have yet been adopted for the civilization and improvement of the aboriginals of America.

They have ever been taught by those who pretended a wish for their improvement that they regarded them as beings of an inferior class to that of their more polished neighbors, as designed merely to complete the nice gradation from the most sagacious of the brute creation to intelligent man.

If this has not been the language of their theory, it certainly has been of their practice. The progress of civilization among the aboriginals has been very little beneficial to the subjects of it, or conducive to their happiness.

We are only taught enough to see and to deplore our forlorn condition. We have lost that independence of character and sentiment, that high sense of personal liberty, that happy equality, and that simplicity of manners which distinguishes rude tribes without acquiring the privileges of civilized societies. Rob a man of his liberty, and you destroy the best part of his nature.

Give us an opportunity to dilate and extend our views in the occupations and pursuits of social life; in the projects of ambition; and the acquisition of wealth; inform our minds with rational science; teach us by bestowing some marks of regard on us to respect ourselves; let us enjoy some portion of civil liberty, and we believe that we should act no inglorious part on the theatre of action.

Even disgusted as we are at present, we flatter ourselves that we are not useless members of the community. With the lance and the harpoon, we wage war with the mighty monsters of the deep; alternately scorching beneath the equatorial heat of the sun, and shivering in the frozen regions of the north to increase the wealth and the commerce of this country.

We will not, however, longer take up the time of the Legislature. We submit the above to their wise consideration, relying on the justice and the equity of their future arrangements respecting us. If we can have no more, we can at least ask to be restored to as free a government as that were subject to before the Revolution.

And as in duty bound shall ever pray, etc.,

Noah Webquish, his mark

Isaac Amos, his mark

Ebenezer Queppish, his mark

Solomon Webquish

Simon Keeter

Jacob Keeter

Nathan Pocknet

Hosea Richards

Moses Keeter

Zaccheus Pocknet

Benjamin Pocknet

Simon Ned

S[ illegible ] G[ illegible ], [ illegible] mark

Isaac Halfday, his mark

Peter Isaac, his mark

John Chummuck

Abraham Mingo

Windsor George, his mark

Joseph Webquish, his mark

Amos Babcock, his mark

Thomas Nunnekins

Gideon Nautumpum, Jr.

_________________

Top image: A painting of the Battle of Quebec in 1775 (Wikimedia Commons)/The Atlantic

For further information about Mashpee Revolutionary War military service, read Jacob Denny, “The Service if the Mashpee Indians in the American Revolution,” December 21, 2011, Tufts Digital Library, http://hdl.handle.net/10427/77461.